If the observer forgets about it, it may sink without him noticing, so he does not know how much time has elapsed. So I made this device so that he will know from the pipe that the boat has sunk, and will wake from his doze at the sound.

al-Jazari

A friend who works as an art conservator once explained to me how her work is fundamentally about slow destruction. If a painting were to be stored in a pitch-black cave, the lack of light would ensure that the vibrancy of the colours would never be lost. Visible light is the enemy of visual art. When it hits a painting and reflects back towards a viewer, that action is slowly but steadily removing the colour, ensuring that it will one day fade away. The very act of making the painting visible, of looking, studying, dismissing, enjoying, hating, or feeling uncertain about a painting is the very act that is also destroying it. A painting can not be perceived without also ceasing to exist. And so art conservation is about managing this inevitable decline, balancing preservation against the need for a painting or tapestry or fresco to be seen and slowly die.

Sound is inherently transient, it passes through us and moves beyond us and is gone. In many ways sound is the form of media that is most illustrative of time, as we can only listen to a sound in the time it takes to hear it – we can glance quickly at a painting or scrub through a video but we can not speed up a sound without changing it fundamentally. The act of listening is about succumbing to the demands a sound will make on our time. We need to give in to this, because the sound will pass, it will create a burst of energy that will expand in a glorious set of vibrations which will fade nearly as quickly as they began. So whilst sound is perhaps not inherently auto-destructive like paintings, it is fleeting.

All things are fleeting, of course. The paintings we look at, the sofa I’m sitting on, the eyeglasses I’m looking through, the coffee I’m drinking, these things will all disappear in the next few minutes or few hundred years. Every person who ever reads this will one day be gone, and all devices that were used to host and access this website will be gone too. It’s nice to try and keep that in mind.

There’s a wonderful phrase in British English, usually applied to postage stamp sized back gardens or a picnic table crammed onto a patio outside a pub: “It’s a real sun trap.” Sunshine, within the context of British culture, is something that needs to be caught before it can flee and disappear from our lives forever. It must be captured for our enjoyment, exploited for everything that it is worth. It’s a phrase that somehow sums up a futile attempt to make light and life last longer than the British weather and our fragile bodies will allow.

Capturing sound, or indeed any form of media, is its own special exercise in futility. We are collectively capturing and storing enormous amounts of sound, video, and photographs, trying to make records of everything we possibly can. The nature of sound makes this particularly problematic, as it is virtually impossible to listen back to everything that I have recorded – it simply takes too much time. I have made far more sound recordings than I could possibly listen back to. I’ve fallen into something of a sound trap.

There is something in the process of recording a moment which lends it an artificial weight. It is supremely difficult to delete a photograph of a loved one or a cherished instant, even if we have dozens of others from that same moment. And yet what of all the moments that were not photographed? What about all of the sounds I didn’t record? Are they not worthy of an emotional bond? Perhaps it is so hard to destroy what we have saved because we feel that they are saving us from something.

Making recordings, taking photographs, recording videos – these things satisfy my brain, providing me with the opportunity to outsource my memories to a phone, a computer, a hard drive, or the ‘cloud’ (or all four). When I outsource my memories I can relax, I don’t need to worry that life is moving faster than I can perceive it, that perhaps I have not fully appreciated the last dog walk or sandwich or hug. I captured these things in my sound trap, I sent them to the cloud, where I will one day hear them and experience them again, for I too will one day go to the clouds.

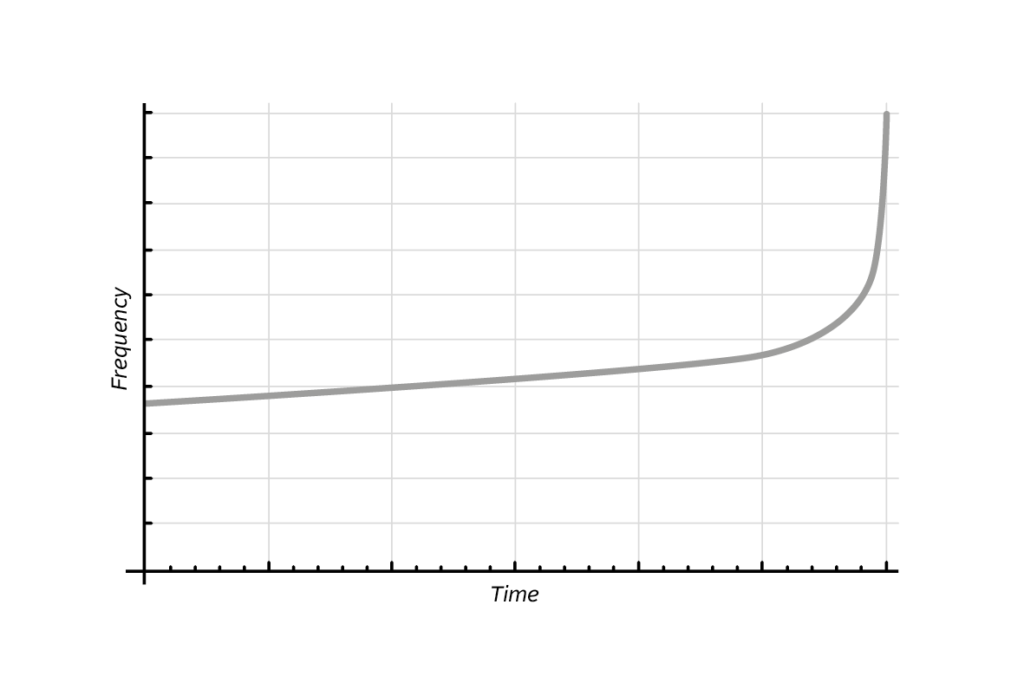

A billion years ago two black holes collided, creating a gravitational wave that was broadcast across the universe. Sensors picked up this wave in September 2015 and translated them into a chirp, the adorable death rattle of two unimaginably gigantic dying stars destroying each other long before all human life on earth. Listening to that wave we are hearing something that has already passed, which on a micro level is of course the case of every sound. When we hear a sound the event that produced it is already over, we are simply hearing the effects of the energy produced. We are perceiving the byproduct of life, and we cling to this by making a recording of it so we can feel that the event itself has not passed. But by the time we listen to a sound, it is gone.

This raises uncomfortable questions, and this is a project about uncomfortable questions. How can I change my approach to listening to recorded sound, how can I force myself to reckon with the idea that the sounds that were made have actually disappeared, that the moment in which that energy was created has passed, that time has moved forward and I will not have that experience ever again? How, in fact, can I make listening to a sound the same as looking at a painting, so every time it is perceived some part of it is also lost? What if each time a sound is heard it is simultaneously destroyed?

This instrument contains a sound. It is a sound that exists no where else – therein lies one challenge. The sound is recorded directly into the instrument itself, with no intermediaries. The recording of the sound is an integral part of the instrument itself, for if the sound exists elsewhere then its destruction carries no real meaning or weight. For the instrument to function the act of listening must also be one of permanent change and destruction, so there must be complete certainty that the sound does not exist anywhere in the world.

The nature of the destruction must also be carefully considered. My first attempt at this involved a system which would place small points of random noise in the sound file at the conclusion of each play. This was remarkably ineffective, as the result did not sound destroyed, but simply included a layer of noise that ears could easily filter out. The added noise even seemed to frame the original sound, like vinyl crackle, allowing the brain to focus even more strongly on it. A different approach was required.

The most effective way to destroy a sound, it turns out, is to use the sound against itself. Slice tiny pieces out of it and place them somewhere else, reversed, or pitched up, slow down a section momentarily before jumping to the end for a few milliseconds, and then continue where you left off. Turn the sound inward, break it apart, jumble the memory of the moment until you can’t remember what it sounded like; did the giggle come first? Or the clapping? Was there a word in there, did he even know how to speak then?

This method is powerful even for sounds that have no personal meaning. A simple snare drum sound, played on loop and destroyed, will suddenly take on a poignant life as it succumbs to a sea of noise and eventually dies away, leaving just a memory of the sound.

With a meaningful sound this process becomes almost unbearable. When the playback, and destruction, is attached to a button the very act of pressing play becomes a loaded decision. Do I really need to hear this sound now? How many more listens will I get before the sound is gone forever? Can I still remember the moment when I recorded this sound? How many times have I listened to it now? When did I record it – it wasn’t that long ago, was it? Why do I feel the need to keep listening to this sound, knowing that each time it is played some part of it is lost?

The sound is slipping away from me, just like the memory of that moment is slipping away and my children are slipping away and my life is slipping away and all life is slipping away from the ever expanding universe. I pointed a microphone at a moment once, I was there and I captured it, but by the time the sound had hit the microphones the moment had already passed, and in order to fully understand it I need to know that it is gone.